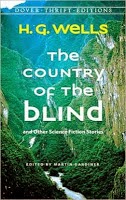

"In the Country of the Blind the One-Eyed Man is King." بلد العميان

كتبت هذه القصة عام 1904 وتحكي عن مجموعة من المهاجرين من بيرو فروا من طغيان الإسبان ثم حدثت انهيارات صخرية في جبال الإنديز فعزلت هؤلاء القوم في واد غامض..

انتشر بينهم نوع غامض من التهاب العيون أصابهم جميعا بالعمي وقد فسروا ذلك بانتشار الخطايا بينهم.

هكذا لم يزر أحد هؤلاء القوم ولم يغادروا واديهم قط لكنهم ورثوا أبناءهم العمي جيلا بعد جيل

هنا يظهر بطل قصتنا (نيونز)

إنه مستكشف وخبير في تسلق الجبال تسلق جبال الانديز مع مجموعة من البريطانيين وفي الليل انزلقت قدمه فسقط من أعلي سقط مسافة شاسعة بحيث لم يعودوا يرون الوادي الذي سقط فيه ولم يعرفوا أنه وادي العميان الأسطوري.

لكن الرجل لم يمت لقد سقط فوق وسادة ثلجية حفظت حياته.

وعندما بدأ المشي علي قدمين متألمتين رأي البيوت التي تملأ الوادي. لاحظ أن ألوانها فاقعة متعددة بشكل غريب ولم تكن لها نوافذ هنا خطر له أن من بني هذه البيوت أعمي كخفاش.

راح يصرخ وينادي الناس لكنهم لم ينظروا نحوه. هنا تأكد من أنهم عميان فعلا إذن هذا هو بلد العميان الذي كان يسمع عنه وتذكر المقولة الشهيرة:

ـ"في بلد العميان يصير الأعور ملكا"

وهو ما يشبه قولنا (أعرج في حارة المكسحين). راح يشرح لهم من أين جاء جاء من بوجاتا حيث يبصر الناس هنا ظهرت مشكلة. ما معني (يبصر)

راحوا يتحسسون وجهه ويغرسون أصابعهم في عينه بدت لهم عضوا غريبا جدا. ولما تعثر أثناء المشي قدروا أنه ليس علي ما يرام حواسه ضعيفة ويقول أشياء غريبة.

يأخذونه لكبيرهم هنا يدرك أنهم يعيشون حياتهم في ظلام دامس وبالتالي هو أكثر شخص ضعيف في هذا المجتمع. لقد مر علي العميان خمسة عشر جيلا وبالتالي صار عالمنا هو الأقرب إلي الأساطير.

عرف فلسفتهم العجيبة هناك ملائكة تسمعها لكن لا تقدر علي لمسها (يتكلمون عن الطيور طبعا) والزمن يتكون من جزءين: بارد ودافئ (المعادل الحسي لليل والنهار) ينام المرء في الدافئ ويعمل في البارد.

لم يكن لدي (نيونز) شك في أنه بلغ المكان الذي سيكون فيه ملكا سيسود هؤلاء القوم بسهولة تامة.

لكن الأمر ظل صعبا إنهم يعرفون كل شيء بآذانهم يعرفون متي مشي علي العشب أو الصخور. كانوا كذلك يستعملون أنوفهم ببراعة تامة.

راح يحكي لهم عن جمال الجبال والغروب والشمس. هم يصغون له باسمين ولا يصدقون حرفا. قرر أن يريهم أهمية البصر. رأي المدعو بدرو قادما من بعيد فقال لهم:

ـ"بدرو سيكون هنا حالا. أنتم لا تسمعونه ولا تشمون رائحته لكني أراه"

بدا عليهم الشك وراحوا ينتظرون. هنا لسبب ما قرر بدرو أن يغير مساره ويبتعد !.

راح يحكي لهم ما يحدث أمام المنازل لكنهم طلبوا منه أن يحكي لهم ما يحدث بداخلها. ألست تزعم أن البصر مهم

حاول الهرب لكنهم لحقوا به بطريقة العميان المخيفة. كانوا يصغون ويتشممون الهواء ويغلقون دائرة من حوله. لو ضرب عددا منهم لاعترفوا بقوته لكن لابد أن ينام بعد هذا وعندها سوف !

هكذا بعد الفرار ليوم كامل في البرد والجوع وجد نفسه يعود لهم ويعتذر وقال لهم:

ـ"أعترف بأنني غير ناضج. لا يوجد شيء اسمه البصر."

كانوا طيبي القلب وصفحوا عنه بسرعة فقط قاموا بجلده ثم كلفوه ببعض الأعمال. وفي هذا الوقت بدأ يميل لفتاة وجدها جميلة لكن العميان لم يكونوا يحبونها لأن وجهها حاد بلا منحنيات ناعمة وصوتها عال وأهدابها طويلة.

أي انها تخالف فكرتهم عن الجمال.

لما طلب يدها لم يقبل أبوها لأنهم كانوا يعتبرونه أقل من مستوي البشر. نوعا من المجاذيب. لكن الفتاة كانت تميل لنيونز فعلا. ووجد الأب نفسه في مشكلة لذا طلب رأي الحكماء.

كان رأي الحكماء قاطعا. الفتي عنده شيئان غريبان منتفخان يسميهما (العينين). جفناه يتحركان وعليهما أهداب. وهذا العضو المريض قد أتلف مخه. لابد من إزالة هذا العضو الغريب ليسترد الفتي عقله. بالتالي يمكنه أن يتزوج الفتاة.

بالطبع ملأ الفتي الدنيا صراخا. لن يضحي بعينيه بأي ثمن. بعد قليل ارتمت الفتاة علي صدره وبكت وهمست: ليتك تقبل. ليتك تقبل!

هكذا صار العمي شرطا ليرتفع المرء من مرتبة الانحطاط ليصير مواطنا كاملا. وقد قبل نيونز أخيرا وبدأ آخر أيامه مع حاسة البصر.

خرج ليري العالم للمرة الأخيرة هنا رأي الفجر يغمر الوادي بلونه الساحر. أدرك أن حياته هنا لطخة آثمة.الأنهار والغابات والأزرق في السماء والنجوم. كيف يفقد هذا كله من أجل فتاة. كيف ولماذا أقنعوه أن البصر شيء لا قيمة له برغم أن هذا خطأ

اتجه إلي حاجز الجبال حيث توجد مدخنة حجرية تتجه لأعلي. وقرر أن يتسلق.

عندما غربت الشمس كان بعيدا جدا عن بلد العميان.

نزفت كفاه وتمزقت ثيابه لكنه كان يبتسم. رفع عينيه وراح يرمق النجوم.

By H.G. Wells

Three hundred

miles and more from Chimborazo, one hundred from the snows of Cotopaxi, in the

wildest wastes of Ecuador's Andes, there lies that mysterious mountain valley,

cut off from all the world of men, the Country of the Blind. Long years ago

that valley lay so far open to the world that men might come at last through

frightful gorges and over an icy pass into its equable meadows, and thither

indeed men came, a family or so of Peruvian half-breeds fleeing from the lust

and tyranny of an evil Spanish ruler. Then came the stupendous outbreak of

Mindobamba, when it was night in Quito for seventeen days, and the water was

boiling at Yaguachi and all the fish floating dying even as far as Guayaquil;

everywhere along the Pacific slopes there were land-slips and swift thawings

and sudden floods, and one whole side of the old Arauca crest slipped and came

down in thunder, and cut off the Country of the Blind for ever from the

exploring feet of men. But one of these early settlers had chanced to be on the

hither side of the gorges when the world had so terribly shaken itself, and he

perforce had to forget his wife and his child and all the friends and

possessions he had left up there, and start life over again in the lower world.

He started it again but ill, blindness overtook him, and he died of punishment

in the mines; but the story he told begot a legend that lingers along the

length of the Cordilleras of the Andes to this day.

He told of

his reason for venturing back from that fastness, into which he had first been

carried lashed to a llama, beside a vast bale of gear, when he was a child. The

valley, he said, had in it all that the heart of man could desire--sweet water,

pasture, an even climate, slopes of rich brown soil with tangles of a shrub

that bore an excellent fruit, and on one side great hanging forests of pine

that held the avalanches high. Far overhead, on three sides, vast cliffs of

grey-green rock were capped by cliffs of ice; but the glacier stream came not

to them, but flowed away by the farther slopes, and only now and then huge ice

masses fell on the valley side. In this valley it neither rained nor snowed,

but the abundant springs gave a rich green pasture, that irrigation would

spread over all the valley space. The settlers did well indeed there. Their

beasts did well and multiplied, and but one thing marred their happiness. Yet

it was enough to mar it greatly. A strange disease had come upon them and had

made all the children born to them there--and, indeed, several older children

also--blind. It was to seek some charm or antidote against this plague of

blindness that he had with fatigue and danger and difficulty returned down the

gorge. In those days, in such cases, men did not think of germs and infections,

but of sins, and it seemed to him that the reason of this affliction must he in

the negligence of these priestless immigrants to set up a shrine so soon as

they entered the valley. He wanted a shrine--a handsome, cheap, effectual

shrine--to be erected in the valley; he wanted relics and such-like potent

things of faith, blessed objects and mysterious medals and prayers. In his

wallet he had a bar of native silver for which he would not account; he

insisted there was none in the valley with something of the insistence of an

inexpert liar. They had all clubbed their money and ornaments together, having

little need for such treasure up there, he said, to buy them holy help against

their ill. I figure this dim-eyed young mountaineer, sunburnt, gaunt, and

anxious, hat brim clutched feverishly, a man all unused to the ways of the

lower world, telling this story to some keen-eyed, attentive priest before the

great convulsion; I can picture him presently seeking to return with pious and

infallible remedies against that trouble, and the infinite dismay with which he

must have faced the tumbled vastness where the gorge had once come out. But the

rest of his story of mischances is lost to me, save that I know of his evil

death after several years. Poor stray from that remoteness! The stream that had

once made the gorge now bursts from the mouth of a rocky cave, and the legend

his poor, ill-told story set going developed into the legend of a race of blind

men somewhere "over there" one may still hear to-day.

And amidst

the little population of that now isolated and forgotten valley the disease ran

its course. The old became groping, the young saw but dimly, and the children

that were born to them never saw at all. But life was very easy in that

snow-rimmed basin, lost to all the world, with neither thorns nor briers, with

no evil insects nor any beasts save the gentle breed of llamas they had lugged

and thrust and followed up the beds of the shrunken rivers in the gorges up

which they had come. The seeing had become purblind so gradually that they

scarcely noticed their loss. They guided the sightless youngsters hither and

thither until they knew the whole valley marvellously, and when at last sight

died out among them the race lived on. They had even time to adapt themselves

to the blind control of fire, which they made carefully in stoves of stone.

They were a simple strain of people at the first, unlettered, only slightly

touched with the Spanish civilisation, but with something of a tradition of the

arts of old Peru and of its lost philosophy. Generation followed generation.

They forgot many things; they devised many things. Their tradition of the

greater world they came from became mythical in colour and uncertain. In all

things save sight they were strong and able, and presently chance sent one who

had an original mind and who could talk and persuade among them, and then

afterwards another. These two passed, leaving their effects, and the little

community grew in numbers and in understanding, and met and settled social and

economic problems that arose. Generation followed generation. Generation

followed generation. There came a time when a child was born who was fifteen

generations from that ancestor who went out of the valley with a bar of silver

to seek God's aid, and who never returned. Thereabout it chanced that a man

came into this community from the outer world. And this is the story of that

man.

He was a

mountaineer from the country near Quito, a man who had been down to the sea and

had seen the world, a reader of books in an original way, an acute and

enterprising man, and he was taken on by a party of Englishmen who had come out

to Ecuador to climb mountains, to replace one of their three Swiss guides who

had fallen ill. He climbed here and he climbed there, and then came the attempt

on Parascotopetl, the Matterhorn of the Andes, in which he was lost to the

outer world. The story of that accident has been written a dozen times.

Pointer's narrative is the best. He tells how the little party worked their

difficult and almost vertical way up to the very foot of the last and greatest

precipice, and how they built a night shelter amidst the snow upon a little

shelf of rock, and, with a touch of real dramatic power, how presently they

found Nunez had gone from them. They shouted, and there was no reply; shouted

and whistled, and for the rest of that night they slept no more.

As the

morning broke they saw the traces of his fall. It seems impossible he could

have uttered a sound. He had slipped eastward towards the unknown side of the

mountain; far below he had struck a steep slope of snow, and ploughed his way

down it in the midst of a snow avalanche. His track went straight to the edge

of a frightful precipice, and beyond that everything was hidden. Far, far

below, and hazy with distance, they could see trees rising out of a narrow,

shut-in valley--the lost Country of the Blind. But they did not know it was the

lost Country of the Blind, nor distinguish it in any way from any other narrow

streak of upland valley. Unnerved by this disaster, they abandoned their

attempt in the afternoon, and Pointer was called away to the war before he

could make another attack. To this day Parascotopetl lifts an unconquered

crest, and Pointer's shelter crumbles unvisited amidst the snows.

And the man

who fell survived.

At the end of

the slope he fell a thousand feet, and came down in the midst of a cloud of

snow upon a snow-slope even steeper than the one above. Down this he was

whirled, stunned and insensible, but without a bone broken in his body; and

then at last came to gentler slopes, and at last rolled out and lay still,

buried amidst a softening heap of the white masses that had accompanied and

saved him. He came to himself with a dim fancy that he was ill in bed; then

realized his position with a mountaineer's intelligence and worked himself

loose and, after a rest or so, out until he saw the stars. He rested flat upon

his chest for a space, wondering where he was and what had happened to him. He

explored his limbs, and discovered that several of his buttons were gone and

his coat turned over his head. His knife had gone from his pocket and his hat

was lost, though he had tied it under his chin. He recalled that he had been

looking for loose stones to raise his piece of the shelter wall. His ice-axe

had disappeared.

He decided he

must have fallen, and looked up to see, exaggerated by the ghastly light of the

rising moon, the tremendous flight he had taken. For a while he lay, gazing

blankly at the vast, pale cliff towering above, rising moment by moment out of

a subsiding tide of darkness. Its phantasmal, mysterious beauty held him for a

space, and then he was seized with a paroxysm of sobbing laughter . . . .

After a great

interval of time he became aware that he was near the lower edge of the snow.

Below, down what was now a moon-lit and practicable slope, he saw the dark and

broken appearance of rock-strewn turf He struggled to his feet, aching in every

joint and limb, got down painfully from the heaped loose snow about him, went

downward until he was on the turf, and there dropped rather than lay beside a

boulder, drank deep from the flask in his inner pocket, and instantly fell

asleep . . . .

He was

awakened by the singing of birds in the trees far below.

He sat up and

perceived he was on a little alp at the foot of a vast precipice that sloped

only a little in the gully down which he and his snow had come. Over against

him another wall of rock reared itself against the sky. The gorge between these

precipices ran east and west and was full of the morning sunlight, which lit to

the westward the mass of fallen mountain that closed the descending gorge.

Below him it seemed there was a precipice equally steep, but behind the snow in

the gully he found a sort of chimney-cleft dripping with snow-water, down which

a desperate man might venture. He found it easier than it seemed, and came at

last to another desolate alp, and then after a rock climb of no particular

difficulty, to a steep slope of trees. He took his bearings and turned his face

up the gorge, for he saw it opened out above upon green meadows, among which he

now glimpsed quite distinctly a cluster of stone huts of unfamiliar fashion. At

times his progress was like clambering along the face of a wall, and after a

time the rising sun ceased to strike along the gorge, the voices of the singing

birds died away, and the air grew cold and dark about him. But the distant

valley with its houses was all the brighter for that. He came presently to

talus, and among the rocks he noted--for he was an observant man--an unfamiliar

fern that seemed to clutch out of the crevices with intense green hands. He

picked a frond or so and gnawed its stalk, and found it helpful.

About midday

he came at last out of the throat of the gorge into the plain and the sunlight.

He was stiff and weary; he sat down in the shadow of a rock, filled up his

flask with water from a spring and drank it down, and remained for a time,

resting before he went on to the houses.

They were

very strange to his eyes, and indeed the whole aspect of that valley became, as

he regarded it, queerer and more unfamiliar. The greater part of its surface

was lush green meadow, starred with many beautiful flowers, irrigated with

extraordinary care, and bearing evidence of systematic cropping piece by piece.

High up and ringing the valley about was a wall, and what appeared to be a

circumferential water channel, from which the little trickles of water that fed

the meadow plants came, and on the higher slopes above this flocks of llamas

cropped the scanty herbage. Sheds, apparently shelters or feeding-places for

the llamas, stood against the boundary wall here and there. The irrigation

streams ran together into a main channel down the centre of the valley, and

this was enclosed on either side by a wall breast high. This gave a singularly

urban quality to this secluded place, a quality that was greatly enhanced by

the fact that a number of paths paved with black and white stones, and each

with a curious little kerb at the side, ran hither and thither in an orderly

manner. The houses of the central village were quite unlike the casual and

higgledy-piggledy agglomeration of the mountain villages he knew; they stood in

a continuous row on either side of a central street of astonishing cleanness,

here and there their parti-coloured facade was pierced by a door, and not a

solitary window broke their even frontage. They were parti-coloured with

extraordinary irregularity, smeared with a sort of plaster that was sometimes

grey, sometimes drab, sometimes slate-coloured or dark brown; and it was the

sight of this wild plastering first brought the word "blind" into the

thoughts of the explorer. "The good man who did that," he thought,

"must have been as blind as a bat."

He descended

a steep place, and so came to the wall and channel that ran about the valley,

near where the latter spouted out its surplus contents into the deeps of the

gorge in a thin and wavering thread of cascade. He could now see a number of

men and women resting on piled heaps of grass, as if taking a siesta, in the

remoter part of the meadow, and nearer the village a number of recumbent

children, and then nearer at hand three men carrying pails on yokes along a

little path that ran from the encircling wall towards the houses. These latter

were clad in garments of llama cloth and boots and belts of leather, and they

wore caps of cloth with back and ear flaps. They followed one another in single

file, walking slowly and yawning as they walked, like men who have been up all

night. There was something so reassuringly prosperous and respectable in their

bearing that after a moment's hesitation Nunez stood forward as conspicuously

as possible upon his rock, and gave vent to a mighty shout that echoed round

the valley.

The three men

stopped, and moved their heads as though they were looking about them. They

turned their faces this way and that, and Nunez gesticulated with freedom. But

they did not appear to see him for all his gestures, and after a time,

directing themselves towards the mountains far away to the right, they shouted

as if in answer. Nunez bawled again, and then once more, and as he gestured

ineffectually the word "blind" came up to the top of his thoughts.

"The fools must be blind," he said.

When at last,

after much shouting and wrath, Nunez crossed the stream by a little bridge,

came through a gate in the wall, and approached them, he was sure that they

were blind. He was sure that this was the Country of the Blind of which the

legends told. Conviction had sprung upon him, and a sense of great and rather

enviable adventure. The three stood side by side, not looking at him, but with

their ears directed towards him, judging him by his unfamiliar steps. They

stood close together like men a little afraid, and he could see their eyelids

closed and sunken, as though the very balls beneath had shrunk away. There was

an expression near awe on their faces.

"A

man," one said, in hardly recognisable Spanish. "A man it is--a man

or a spirit--coming down from the rocks."

But Nunez

advanced with the confident steps of a youth who enters upon life. All the old

stories of the lost valley and the Country of the Blind had come back to his

mind, and through his thoughts ran this old proverb, as if it were a refrain:--

"In the

Country of the Blind the One-Eyed Man is King."

"In the

Country of the Blind the One-Eyed Man is King."

And very

civilly he gave them greeting. He talked to them and used his eyes.

"Where

does he come from, brother Pedro?" asked one.

"Down

out of the rocks."

"Over

the mountains I come," said Nunez, "out of the country beyond

there--where men can see. From near Bogota--where there are a hundred thousands

of people, and where the city passes out of sight."

"Sight?"

muttered Pedro. "Sight?"

"He

comes," said the second blind man, "out of the rocks."

The cloth of

their coats, Nunez saw was curious fashioned, each with a different sort of

stitching.

They startled

him by a simultaneous movement towards him, each with a hand outstretched. He

stepped back from the advance of these spread fingers.

"Come

hither," said the third blind man, following his motion and clutching him

neatly.

And they held

Nunez and felt him over, saying no word further until they had done so.

"Carefully,"

he cried, with a finger in his eye, and found they thought that organ, with its

fluttering lids, a queer thing in him. They went over it again.

"A

strange creature, Correa," said the one called Pedro. "Feel the

coarseness of his hair. Like a llama's hair."

"Rough

he is as the rocks that begot him," said Correa, investigating Nunez's

unshaven chin with a soft and slightly moist hand. "Perhaps he will grow

finer."

Nunez

struggled a little under their examination, but they gripped him firm.

"Carefully,"

he said again.

"He

speaks," said the third man. "Certainly he is a man."

"Ugh!"

said Pedro, at the roughness of his coat.

"And you

have come into the world?" asked Pedro.

"Out of

the world. Over mountains and glaciers; right over above there, half-way to the

sun. Out of the great, big world that goes down, twelve days' journey to the

sea."

They scarcely

seemed to heed him. "Our fathers have told us men may be made by the

forces of Nature," said Correa. "It is the warmth of things, and

moisture, and rottenness--rottenness."

"Let us

lead him to the elders," said Pedro.

"Shout

first," said Correa, "lest the children be afraid. This is a

marvellous occasion."

So they

shouted, and Pedro went first and took Nunez by the hand to lead him to the

houses.

He drew his

hand away. "I can see," he said.

"See?"

said Correa.

"Yes;

see," said Nunez, turning towards him, and stumbled against Pedro's pail.

"His

senses are still imperfect," said the third blind man. "He stumbles,

and talks unmeaning words. Lead him by the hand."

"As you

will," said Nunez, and was led along laughing.

It seemed

they knew nothing of sight.

Well, all in

good time he would teach them.

He heard

people shouting, and saw a number of figures gathering together in the middle

roadway of the village.

He found it

tax his nerve and patience more than he had anticipated, that first encounter

with the population of the Country of the Blind. The place seemed larger as he

drew near to it, and the smeared plasterings queerer, and a crowd of children

and men and women (the women and girls he was pleased to note had, some of

them, quite sweet faces, for all that their eyes were shut and sunken) came

about him, holding on to him, touching him with soft, sensitive hands, smelling

at him, and listening at every word he spoke. Some of the maidens and children,

however, kept aloof as if afraid, and indeed his voice seemed coarse and rude

beside their softer notes. They mobbed him. His three guides kept close to him

with an effect of proprietorship, and said again and again, "A wild man

out of the rocks."

"Bogota,"

he said. "Bogota. Over the mountain crests."

"A wild

man--using wild words," said Pedro. "Did you hear that--"Bogota?

His mind has hardly formed yet. He has only the beginnings of speech."

A little boy

nipped his hand. "Bogota!" he said mockingly.

"Aye! A

city to your village. I come from the great world --where men have eyes and

see."

"His

name's Bogota," they said.

"He

stumbled," said Correa--" stumbled twice as we came hither."

"Bring

him in to the elders."

And they

thrust him suddenly through a doorway into a room as black as pitch, save at

the end there faintly glowed a fire. The crowd closed in behind him and shut

out all but the faintest glimmer of day, and before he could arrest himself he

had fallen headlong over the feet of a seated man. His arm, outflung, struck

the face of someone else as he went down; he felt the soft impact of features

and heard a cry of anger, and for a moment he struggled against a number of

hands that clutched him. It was a one-sided fight. An inkling of the situation

came to him and he lay quiet.

"I fell

down," be said; I couldn't see in this pitchy darkness."

There was a

pause as if the unseen persons about him tried to understand his words. Then

the voice of Correa said: "He is but newly formed. He stumbles as he walks

and mingles words that mean nothing with his speech."

Others also

said things about him that he heard or understood imperfectly.

"May I

sit up?" he asked, in a pause. "I will not struggle against you

again."

They

consulted and let him rise.

The voice of

an older man began to question him, and Nunez found himself trying to explain

the great world out of which he had fallen, and the sky and mountains and

such-like marvels, to these elders who sat in darkness in the Country of the

Blind. And they would believe and understand nothing whatever that he told

them, a thing quite outside his expectation. They would not even understand

many of his words. For fourteen generations these people had been blind and cut

off from all the seeing world; the names for all the things of sight had faded

and changed; the story of the outer world was faded and changed to a child's

story; and they had ceased to concern themselves with anything beyond the rocky

slopes above their circling wall. Blind men of genius had arisen among them and

questioned the shreds of belief and tradition they had brought with them from

their seeing days, and had dismissed all these things as idle fancies and

replaced them with new and saner explanations. Much of their imagination had

shrivelled with their eyes, and they had made for themselves new imaginations

with their ever more sensitive ears and finger-tips. Slowly Nunez realised

this: that his expectation of wonder and reverence at his origin and his gifts

was not to be borne out; and after his poor attempt to explain sight to them

had been set aside as the confused version of a new-made being describing the

marvels of his incoherent sensations, he subsided, a little dashed, into

listening to their instruction. And the eldest of the blind men explained to

him life and philosophy and religion, how that the world (meaning their valley)

had been first an empty hollow in the rocks, and then had come first inanimate

things without the gift of touch, and llamas and a few other creatures that had

little sense, and then men, and at last angels, whom one could hear singing and

making fluttering sounds, but whom no one could touch at all, which puzzled

Nunez greatly until he thought of the birds.

He went on to

tell Nunez how this time had been divided into the warm and the cold, which are

the blind equivalents of day and night, and how it was good to sleep in the

warm and work during the cold, so that now, but for his advent, the whole town

of the blind would have been asleep. He said Nunez must have been specially

created to learn and serve the wisdom they had acquired, and that for all his

mental incoherency and stumbling behaviour he must have courage and do his best

to learn, and at that all the people in the door-way murmured encouragingly. He

said the night--for the blind call their day night--was now far gone, and it

behooved everyone to go back to sleep. He asked Nunez if he knew how to sleep,

and Nunez said he did, but that before sleep he wanted food. They brought him

food, llama's milk in a bowl and rough salted bread, and led him into a lonely

place to eat out of their hearing, and afterwards to slumber until the chill of

the mountain evening roused them to begin their day again. But Nunez slumbered

not at all.

Instead, he

sat up in the place where they had left him, resting his limbs and turning the

unanticipated circumstances of his arrival over and over in his mind.

Every now and

then he laughed, sometimes with amusement and sometimes with indignation.

"Unformed

mind!" he said. "Got no senses yet! They little know they've been

insulting their Heaven-sent King and master . . . . .

"I see I

must bring them to reason.

"Let me

think.

"Let me

think."

He was still

thinking when the sun set.

Nunez had an

eye for all beautiful things, and it seemed to him that the glow upon the

snow-fields and glaciers that rose about the valley on every side was the most

beautiful thing he had ever seen. His eyes went from that inaccessible glory to

the village and irrigated fields, fast sinking into the twilight, and suddenly

a wave of emotion took him, and he thanked God from the bottom of his heart

that the power of sight had been given him.

He heard a

voice calling to him from out of the village.

"Yaho there,

Bogota! Come hither!"

At that he

stood up, smiling. He would show these people once and for all what sight would

do for a man. They would seek him, but not find him.

"You

move not, Bogota," said the voice.

He laughed

noiselessly and made two stealthy steps aside from the path.

"Trample

not on the grass, Bogota; that is not allowed."

Nunez had

scarcely heard the sound he made himself. He stopped, amazed.

The owner of

the voice came running up the piebald path towards him.

He stepped

back into the pathway. "Here I am," he said.

"Why did

you not come when I called you?" said the blind man. "Must you be led

like a child? Cannot you hear the path as you walk?"

Nunez

laughed. "I can see it," he said.

"There

is no such word as see," said the blind man, after a pause. "Cease

this folly and follow the sound of my feet."

Nunez

followed, a little annoyed.

"My time

will come," he said.

"You'll

learn," the blind man answered. "There is much to learn in the

world."

"Has no

one told you, 'In the Country of the Blind the One-Eyed Man is King?'"

"What is

blind?" asked the blind man, carelessly, over his shoulder.

Four days

passed and the fifth found the King of the Blind still incognito, as a clumsy

and useless stranger among his subjects.

It was, he

found, much more difficult to proclaim himself than he had supposed, and in the

meantime, while he meditated his coup d'etat, he did what he was told and

learnt the manners and customs of the Country of the Blind. He found working

and going about at night a particularly irksome thing, and he decided that that

should be the first thing he would change.

They led a

simple, laborious life, these people, with all the elements of virtue and

happiness as these things can be understood by men. They toiled, but not

oppressively; they had food and clothing sufficient for their needs; they had

days and seasons of rest; they made much of music and singing, and there was

love among them and little children. It was marvellous with what confidence and

precision they went about their ordered world. Everything, you see, had been

made to fit their needs; each of the radiating paths of the valley area had a

constant angle to the others, and was distinguished by a special notch upon its

kerbing; all obstacles and irregularities of path or meadow had long since been

cleared away; all their methods and procedure arose naturally from their

special needs. Their senses had become marvellously acute; they could hear and

judge the slightest gesture of a man a dozen paces away--could hear the very

beating of his heart. Intonation had long replaced expression with them, and

touches gesture, and their work with hoe and spade and fork was as free and

confident as garden work can be. Their sense of smell was extraordinarily fine;

they could distinguish individual differences as readily as a dog can, and they

went about the tending of llamas, who lived among the rocks above and came to

the wall for food and shelter, with ease and confidence. It was only when at

last Nunez sought to assert himself that he found how easy and confident their

movements could be.

He rebelled

only after he had tried persuasion.

He tried at

first on several occasions to tell them of sight. "Look you here, you

people," he said. "There are things you do not understand in

me."

Once or twice

one or two of them attended to him; they sat with faces downcast and ears

turned intelligently towards him, and he did his best to tell them what it was

to see. Among his hearers was a girl, with eyelids less red and sunken than the

others, so that one could almost fancy she was hiding eyes, whom especially he

hoped to persuade. He spoke of the beauties of sight, of watching the

mountains, of the sky and the sunrise, and they heard him with amused incredulity

that presently became condemnatory. They told him there were indeed no

mountains at all, but that the end of the rocks where the llamas grazed was

indeed the end of the world; thence sprang a cavernous roof of the universe,

from which the dew and the avalanches fell; and when he maintained stoutly the

world had neither end nor roof such as they supposed, they said his thoughts

were wicked. So far as he could describe sky and clouds and stars to them it

seemed to them a hideous void, a terrible blankness in the place of the smooth

roof to things in which they believed--it was an article of faith with them

that the cavern roof was exquisitely smooth to the touch. He saw that in some

manner he shocked them, and gave up that aspect of the matter altogether, and

tried to show them the practical value of sight. One morning he saw Pedro in

the path called Seventeen and coming towards the central houses, but still too

far off for hearing or scent, and he told them as much. "In a little

while," he prophesied, "Pedro will be here." An old man remarked

that Pedro had no business on path Seventeen, and then, as if in confirmation,

that individual as he drew near turned and went transversely into path Ten, and

so back with nimble paces towards the outer wall. They mocked Nunez when Pedro

did not arrive, and afterwards, when he asked Pedro questions to clear his

character, Pedro denied and outfaced him, and was afterwards hostile to him.

Then he

induced them to let him go a long way up the sloping meadows towards the wall

with one complaisant individual, and to him he promised to describe all that

happened among the houses. He noted certain goings and comings, but the things

that really seemed to signify to these people happened inside of or behind the

windowless houses--the only things they took note of to test him by--and of

those he could see or tell nothing; and it was after the failure of this

attempt, and the ridicule they could not repress, that he resorted to force. He

thought of seizing a spade and suddenly smiting one or two of them to earth,

and so in fair combat showing the advantage of eyes. He went so far with that

resolution as to seize his spade, and then he discovered a new thing about

himself, and that was that it was impossible for him to hit a blind man in cold

blood.

He hesitated,

and found them all aware that he had snatched up the spade. They stood all

alert, with their heads on one side, and bent ears towards him for what he

would do next.

"Put

that spade down," said one, and he felt a sort of helpless horror. He came

near obedience.

Then he had

thrust one backwards against a house wall, and fled past him and out of the

village.

He went

athwart one of their meadows, leaving a track of trampled grass behind his

feet, and presently sat down by the side of one of their ways. He felt

something of the buoyancy that comes to all men in the beginning of a fight,

but more perplexity. He began to realise that you cannot even fight happily

with creatures who stand upon a different mental basis to yourself. Far away he

saw a number of men carrying spades and sticks come out of the street of houses

and advance in a spreading line along the several paths towards him. They

advanced slowly, speaking frequently to one another, and ever and again the

whole cordon would halt and sniff the air and listen.

The first

time they did this Nunez laughed. But afterwards he did not laugh.

One struck

his trail in the meadow grass and came stooping and feeling his way along it.

For five

minutes he watched the slow extension of the cordon, and then his vague

disposition to do something forthwith became frantic. He stood up, went a pace

or so towards the circumferential wall, turned, and went back a little way.

There they all stood in a crescent, still and listening.

He also stood

still, gripping his spade very tightly in both hands. Should he charge them?

The pulse in

his ears ran into the rhythm of "In the Country of the Blind the One-Eyed

Man is King."

Should he

charge them?

He looked

back at the high and unclimbable wall behind--unclimbable because of its smooth

plastering, but withal pierced with many little doors and at the approaching

line of seekers. Behind these others were now coming out of the street of

houses.

Should he

charge them?

"Bogota!"

called one. "Bogota! where are you?"

He gripped

his spade still tighter and advanced down the meadows towards the place of

habitations, and directly he moved they converged upon him. "I'll hit them

if they touch me," he swore; "by Heaven, I will. I'll hit." He

called aloud, "Look here, I'm going to do what I like in this valley! Do

you hear? I'm going to do what I like and go where I like."

They were

moving in upon him quickly, groping, yet moving rapidly. It was like playing

blind man's buff with everyone blindfolded except one. "Get hold of

him!" cried one. He found himself in the arc of a loose curve of pursuers.

He felt suddenly he must be active and resolute.

"You

don't understand," he cried, in a voice that was meant to be great and

resolute, and which broke. "You are blind and I can see. Leave me

alone!"

"Bogota!

Put down that spade and come off the grass!"

The last

order, grotesque in its urban familiarity, produced a gust of anger. "I'll

hurt you," he said, sobbing with emotion. "By Heaven, I'll hurt you!

Leave me alone!"

He began to

run--not knowing clearly where to run. He ran from the nearest blind man,

because it was a horror to hit him. He stopped, and then made a dash to escape

from their closing ranks. He made for where a gap was wide, and the men on

either side, with a quick perception of the approach of his paces, rushed in on

one another. He sprang forward, and then saw he must be caught, and swish! the

spade had struck. He felt the soft thud of hand and arm, and the man was down

with a yell of pain, and he was through.

Through! And

then he was close to the street of houses again, and blind men, whirling spades

and stakes, were running with a reasoned swiftness hither and thither.

He heard

steps behind him just in time, and found a tall man rushing forward and swiping

at the sound of him. He lost his nerve, hurled his spade a yard wide of this

antagonist, and whirled about and fled, fairly yelling as he dodged another.

He was

panic-stricken. He ran furiously to and fro, dodging when there was no need to

dodge, and, in his anxiety to see on every side of him at once, stumbling. For

a moment he was down and they heard his fall. Far away in the circumferential

wall a little doorway looked like Heaven, and he set off in a wild rush for it.

He did not even look round at his pursuers until it was gained, and he had

stumbled across the bridge, clambered a little way among the rocks, to the

surprise and dismay of a young llama, who went leaping out of sight, and lay

down sobbing for breath.

And so his

coup d'etat came to an end.

He stayed

outside the wall of the valley of the blind for two nights and days without

food or shelter, and meditated upon the Unexpected. During these meditations he

repeated very frequently and always with a profounder note of derision the

exploded proverb: "In the Country of the Blind the One-Eyed Man is

King." He thought chiefly of ways of fighting and conquering these people,

and it grew clear that for him no practicable way was possible. He had no

weapons, and now it would be hard to get one.

The canker of

civilisation had got to him even in Bogota, and he could not find it in himself

to go down and assassinate a blind man. Of course, if he did that, he might

then dictate terms on the threat of assassinating them all. But--Sooner or

later he must sleep! . . . .

He tried also

to find food among the pine trees, to be comfortable under pine boughs while

the frost fell at night, and-- with less confidence--to catch a llama by

artifice in order to try to kill it--perhaps by hammering it with a stone--and

so finally, perhaps, to eat some of it. But the llamas had a doubt of him and

regarded him with distrustful brown eyes and spat when he drew near. Fear came

on him the second day and fits of shivering. Finally he crawled down to the

wall of the Country of the Blind and tried to make his terms. He crawled along

by the stream, shouting, until two blind men came out to the gate and talked to

him.

"I was

mad," he said. "But I was only newly made."

They said

that was better.

He told them

he was wiser now, and repented of all he had done.

Then he wept

without intention, for he was very weak and ill now, and they took that as a

favourable sign.

They asked

him if he still thought he could see."

"No,"

he said. "That was folly. The word means nothing. Less than nothing!"

They asked

him what was overhead.

"About

ten times ten the height of a man there is a roof above the world--of rock--and

very, very smooth. So smooth--so beautifully smooth . . "He burst again

into hysterical tears. "Before you ask me any more, give me some food or I

shall die!"

He expected

dire punishments, but these blind people were capable of toleration. They

regarded his rebellion as but one more proof of his general idiocy and

inferiority, and after they had whipped him they appointed him to do the

simplest and heaviest work they had for anyone to do, and he, seeing no other

way of living, did submissively what he was told.

He was ill

for some days and they nursed him kindly. That refined his submission. But they

insisted on his lying in the dark, and that was a great misery. And blind

philosophers came and talked to him of the wicked levity of his mind, and

reproved him so impressively for his doubts about the lid of rock that covered

their cosmic casserole that he almost doubted whether indeed he was not the

victim of hallucination in not seeing it overhead.

So Nunez

became a citizen of the Country of the Blind, and these people ceased to be a

generalised people and became individualities to him, and familiar to him,

while the world beyond the mountains became more and more remote and unreal.

There was Yacob, his master, a kindly man when not annoyed; there was Pedro,

Yacob's nephew; and there was Medina-sarote, who was the youngest daughter of

Yacob. She was little esteemed in the world of the blind, because she had a

clear-cut face and lacked that satisfying, glossy smoothness that is the blind

man's ideal of feminine beauty, but Nunez thought her beautiful at first, and

presently the most beautiful thing in the whole creation. Her closed eyelids

were not sunken and red after the common way of the valley, but lay as though

they might open again at any moment; and she had long eyelashes, which were

considered a grave disfigurement. And her voice was weak and did not satisfy

the acute hearing of the valley swains. So that she had no lover.

There came a

time when Nunez thought that, could he win her, he would be resigned to live in

the valley for all the rest of his days.

He watched

her; he sought opportunities of doing her little services and presently he

found that she observed him. Once at a rest-day gathering they sat side by side

in the dim starlight, and the music was sweet. His hand came upon hers and he

dared to clasp it. Then very tenderly she returned his pressure. And one day,

as they were at their meal in the darkness, he felt her hand very softly

seeking him, and as it chanced the fire leapt then, and he saw the tenderness

of her face.

He sought to

speak to her.

He went to

her one day when she was sitting in the summer moonlight spinning. The light

made her a thing of silver and mystery. He sat down at her feet and told her he

loved her, and told her how beautiful she seemed to him. He had a lover's

voice, he spoke with a tender reverence that came near to awe, and she had

never before been touched by adoration. She made him no definite answer, but it

was clear his words pleased her.

After that he

talked to her whenever he could take an opportunity. The valley became the

world for him, and the world beyond the mountains where men lived by day seemed

no more than a fairy tale he would some day pour into her ears. Very

tentatively and timidly he spoke to her of sight.

Sight seemed

to her the most poetical of fancies, and she listened to his description of the

stars and the mountains and her own sweet white-lit beauty as though it was a

guilty indulgence. She did not believe, she could only half understand, but she

was mysteriously delighted, and it seemed to him that she completely

understood.

His love lost

its awe and took courage. Presently he was for demanding her of Yacob and the

elders in marriage, but she became fearful and delayed. And it was one of her

elder sisters who first told Yacob that Medina-sarote and Nunez were in love.

There was

from the first very great opposition to the marriage of Nunez and

Medina-sarote; not so much because they valued her as because they held him as

a being apart, an idiot, incompetent thing below the permissible level of a

man. Her sisters opposed it bitterly as bringing discredit on them all; and old

Yacob, though he had formed a sort of liking for his clumsy, obedient serf,

shook his head and said the thing could not be. The young men were all angry at

the idea of corrupting the race, and one went so far as to revile and strike

Nunez. He struck back. Then for the first time he found an advantage in seeing,

even by twilight, and after that fight was over no one was disposed to raise a

hand against him. But they still found his marriage impossible.

Old Yacob had

a tenderness for his last little daughter, and was grieved to have her weep

upon his shoulder.

"You

see, my dear, he's an idiot. He has delusions; he can't do anything

right."

"I

know," wept Medina-sarote. "But he's better than he was. He's getting

better. And he's strong, dear father, and kind--stronger and kinder than any

other man in the world. And he loves me--and, father, I love him."

Old Yacob was

greatly distressed to find her inconsolable, and, besides--what made it more

distressing--he liked Nunez for many things. So he went and sat in the

windowless council-chamber with the other elders and watched the trend of the

talk, and said, at the proper time, "He's better than he was. Very likely,

some day, we shall find him as sane as ourselves."

Then

afterwards one of the elders, who thought deeply, had an idea. He was a great

doctor among these people, their medicine-man, and he had a very philosophical

and inventive mind, and the idea of curing Nunez of his peculiarities appealed

to him. One day when Yacob was present he returned to the topic of Nunez.

"I have examined Nunez," he said, "and the case is clearer to

me. I think very probably he might be cured."

"This is

what I have always hoped," said old Yacob.

"His

brain is affected," said the blind doctor.

The elders

murmured assent.

"Now,

what affects it?"

"Ah!"

said old Yacob.

This,"

said the doctor, answering his own question. "Those queer things that are

called the eyes, and which exist to make an agreeable depression in the face,

are diseased, in the case of Nunez, in such a way as to affect his brain. They

are greatly distended, he has eyelashes, and his eyelids move, and consequently

his brain is in a state of constant irritation and distraction."

"Yes?"

said old Yacob. "Yes?"

"And I

think I may say with reasonable certainty that, in order to cure him complete,

all that we need to do is a simple and easy surgical operation--namely, to

remove these irritant bodies."

"And

then he will be sane?"

"Then he

will be perfectly sane, and a quite admirable citizen."

"Thank

Heaven for science!" said old Yacob, and went forth at once to tell Nunez

of his happy hopes.

But Nunez's

manner of receiving the good news struck him as being cold and disappointing.

"One

might think," he said, "from the tone you take that you did not care

for my daughter."

It was

Medina-sarote who persuaded Nunez to face the blind surgeons.

"You do

not want me," he said, "to lose my gift of sight?"

She shook her

head.

"My

world is sight."

Her head

drooped lower.

"There

are the beautiful things, the beautiful little things--the flowers, the lichens

amidst the rocks, the light and softness on a piece of fur, the far sky with

its drifting dawn of clouds, the sunsets and the stars. And there is you. For

you alone it is good to have sight, to see your sweet, serene face, your kindly

lips, your dear, beautiful hands folded together. . . . . It is these eyes of

mine you won, these eyes that hold me to you, that these idiots seek. Instead,

I must touch you, hear you, and never see you again. I must come under that

roof of rock and stone and darkness, that horrible roof under which your

imaginations stoop . . . no; you would not have me do that?"

A

disagreeable doubt had arisen in him. He stopped and left the thing a question.

"I

wish," she said, "sometimes--" She paused.

"Yes?"

he said, a little apprehensively.

"I wish

sometimes--you would not talk like that."

"Like

what?"

"I know

it's pretty--it's your imagination. I love it, but now--"

He felt cold.

"Now?" he said, faintly.

She sat quite

still.

"You

mean--you think--I should be better, better perhaps--"

He was

realising things very swiftly. He felt anger perhaps, anger at the dull course

of fate, but also sympathy for her lack of understanding--a sympathy near akin

to pity.

"Dear,"

he said, and he could see by her whiteness how tensely her spirit pressed

against the things she could not say. He put his arms about her, he kissed her

ear, and they sat for a time in silence.

"If I

were to consent to this?" he said at last, in a voice that was very

gentle.

She flung her

arms about him, weeping wildly. "Oh, if you would," she sobbed,

"if only you would!"

For a week

before the operation that was to raise him from his servitude and inferiority

to the level of a blind citizen Nunez knew nothing of sleep, and all through

the warm, sunlit hours, while the others slumbered happily, he sat brooding or

wandered aimlessly, trying to bring his mind to bear on his dilemma. He had

given his answer, he had given his consent, and still he was not sure. And at

last work-time was over, the sun rose in splendour over the golden crests, and

his last day of vision began for him. He had a few minutes with Medina-sarote

before she went apart to sleep.

"To-morrow,"

he said, "I shall see no more."

"Dear

heart!" she answered, and pressed his hands with all her strength.

"They

will hurt you but little," she said; "and you are going through this

pain, you are going through it, dear lover, for me . . . . Dear, if a woman's

heart and life can do it, I will repay you. My dearest one, my dearest with the

tender voice, I will repay."

He was

drenched in pity for himself and her.

He held her

in his arms, and pressed his lips to hers and looked on her sweet face for the

last time. "Good-bye!" he whispered to that dear sight,

"good-bye!"

And then in

silence he turned away from her.

She could

hear his slow retreating footsteps, and something in the rhythm of them threw

her into a passion of weeping.

He walked

away.

He had fully

meant to go to a lonely place where the meadows were beautiful with white

narcissus, and there remain until the hour of his sacrifice should come, but as

he walked he lifted up his eyes and saw the morning, the morning like an angel

in golden armour, marching down the steeps . . . .

It seemed to

him that before this splendour he and this blind world in the valley, and his

love and all, were no more than a pit of sin.

He did not

turn aside as he had meant to do, but went on and passed through the wall of

the circumference and out upon the rocks, and his eyes were always upon the

sunlit ice and snow.

He saw their

infinite beauty, and his imagination soared over them to the things beyond he

was now to resign for ever!

He thought of

that great free world that he was parted from, the world that was his own, and

he had a vision of those further slopes, distance beyond distance, with Bogota,

a place of multitudinous stirring beauty, a glory by day, a luminous mystery by

night, a place of palaces and fountains and statues and white houses, lying

beautifully in the middle distance. He thought how for a day or so one might

come down through passes drawing ever nearer and nearer to its busy streets and

ways. He thought of the river journey, day by day, from great Bogota to the

still vaster world beyond, through towns and villages, forest and desert

places, the rushing river day by day, until its banks receded, and the big

steamers came splashing by and one had reached the sea--the limitless sea, with

its thousand islands, its thousands of islands, and its ships seen dimly far

away in their incessant journeyings round and about that greater world. And

there, unpent by mountains, one saw the sky--the sky, not such a disc as one

saw it here, but an arch of immeasurable blue, a deep of deeps in which the

circling stars were floating . . . .

His eyes

began to scrutinise the great curtain of the mountains with a keener inquiry.

For example;

if one went so, up that gully and to that chimney there, then one might come

out high among those stunted pines that ran round in a sort of shelf and rose

still higher and higher as it passed above the gorge. And then? That talus

might be managed. Thence perhaps a climb might be found to take him up to the

precipice that came below the snow; and if that chimney failed, then another

farther to the east might serve his purpose better. And then? Then one would be

out upon the amber-lit snow there, and half-way up to the crest of those

beautiful desolations. And suppose one had good fortune!

He glanced

back at the village, then turned right round and regarded it with folded arms.

He thought of

Medina-sarote, and she had become small and remote.

He turned

again towards the mountain wall down which the day had come to him.

Then very

circumspectly he began his climb.

When sunset

came he was not longer climbing, but he was far and high. His clothes were

torn, his limbs were bloodstained, he was bruised in many places, but he lay as

if he were at his ease, and there was a smile on his face.

From where he

rested the valley seemed as if it were in a pit and nearly a mile below.

Already it was dim with haze and shadow, though the mountain summits around him

were things of light and fire. The mountain summits around him were things of

light and fire, and the little things in the rocks near at hand were drenched

with light and beauty, a vein of green mineral piercing the grey, a flash of

small crystal here and there, a minute, minutely-beautiful orange lichen close

beside his face. There were deep, mysterious shadows in the gorge, blue

deepening into purple, and purple into a luminous darkness, and overhead was

the illimitable vastness of the sky. But he heeded these things no longer, but

lay quite still there, smiling as if he were content now merely to have escaped

from the valley of the Blind, in which he had thought to be King. And the glow

of the sunset passed, and the night came, and still he lay there, under the

cold, clear stars.

Literature

Network » H.G. Wells » The Country of the Blind

قصة (البروز) من الكتاب الأول لتيسير نظمي:خارطة للموتى خارطة للوطن - كتاب البحث عن مساحة - دار الطليعة 1979

Short story written by Tayseer Nazmi in 1977

Extracted from his first book

(Quest For An Area)

Kuwait 1979

.jpg)

تعليقات